...The NCAA has historically limited college athletes’ compensation to tuition, room, board and, in the wake of a 2021 Supreme Court decision, small grants. Even with that modest augmentation, the NCAA rules—set against schools’ brimming coffers—have created a divide.

In 2022, Power Five athletic departments spent an average of $53 million on coaches and staff across all sports but just $18 million on financial support for athletes. That’s according to financial data from dozens of the nation’s biggest athletic departments gathered by the Knight-Newhouse College Athletics Database and analyzed by The Wall Street Journal.

Michigan, for instance, spent $75 million on coaches and staff in 2022, compared with $33 million on athlete aid and meals. The athletic department has about 350 staff members and 950 athletes.

The figures don’t include endorsement deals—money that comes from outside of the school—that coaches or athletes sign. Such deals for athletes let them earn compensation—and for big stars, windfalls—in recent years for the first time. But NCAA rules still maintain one philosophical red line, that schools can never pay athletes to play for them.

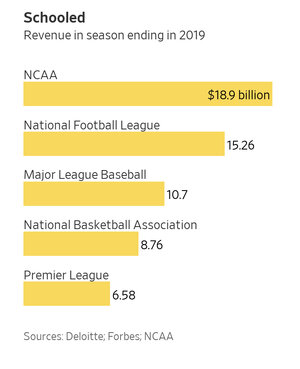

The gap between what colleges pay coaches and what they allocate in athlete funding provides a dramatic backdrop to the rising pressure for college athletes to be paid, and specifically out of the billions of dollars generated by their sports. A wave of lawsuits is also contributing to the push, with various cases working their way through courts around the country. Any one of them could result in a decision that forces pay for players.

The furthest along is a federal case in California, in which past players are suing for damages in the form of lost endorsement money at a time when the NCAA banned such deals, and which also argues that players should have access to a portion of television rights deals worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Both claims rest on an idea that has increasingly vocal support from judges all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, and within the Justice Department—that the NCAA’s longstanding rules severely restricting athlete compensation may not withstand antitrust scrutiny.

Even the NCAA is starting to feel the force, with association president Charlie Baker recently unveiling

a proposal that would let top athletics departments pay athletes directly through their own endorsement deals and trust funds. The move remains an idea at the moment, and would need to be approved by NCAA member schools. In the past, hundreds of smaller programs have balked at radical changes to the school-athlete relationship. The proposal marks a radical shift from the top of an organization that for decades had clung to the notion that college sports couldn’t survive its athletes being paid to play...

...That college football coaches have changed where they stand on this issue is especially notable because they have the most to lose in future contracts should athletes gain a share of revenue. From Saban’s

$11.4 million annual pay to Swinney’s $10.9 million and Brian Kelly’s $10 million, they’re among the highest-paid coaches in all of sports.

Those coaches’ perspectives also pit them against college athletic conferences, which have lined up against revenue-sharing, including

lobbying the U.S. Congress for a federal law that would block any attempts by states to mandate it. Conference lobbyists have told U.S. lawmakers that revenue-sharing requirements could change the familiar look of college sports and result in some sports being cut.

At a preseason media event last summer, Southeastern Conference commissioner Greg Sankey said that revenue-sharing efforts “create new threats around the support of Olympic and women’s sports….

And our primary objective is to continue these broad-based, widespread opportunities through experiences, friendships, learning opportunities, competitive opportunities that are inherent in the higher education setting in a continuing focus for those of us in college athletics.”

But in California, activists continue to push a bill that would require universities in the state to use all new athletic revenue generated by sports such as football and basketball to pay players. Legislation passed the state assembly in the summer, before stalling in the state senate amid an all-out effort by the conferences to block it. Advocates have vowed to revive the effort in the middle of next year.

Supporters and opponents of revenue-sharing alike have viewed legislative efforts in California as having the power to make the rest of the country follow. “Something’s going to happen,” said

Ramogi Huma, a former UCLA football player who has spent two decades pursuing compensation and protections for college players, and is the architect of the California push. “Once the monopoly is broken, the schools have to keep up.”