TuffaloDeac10

🌹☭

I don't think this is getting enough attention.

The IMF has released their new World Economic Outlook. It's gloomy, but there's a fascinating (maybe?) bit at the end of Chapter 1 - Box 1.1, "Are We Underestimating Short-Term Fiscal Multipliers?," co-written by the IMF's chief economist - that deals with the all-important fiscal multiplier. Essentially, Keynesians believe that multipliers are larger than 1 at certain times and government spending will boost economic output in those conditions. If you can spend $100B to get, say, a 125B increase in GDP, that's a good deal. Austerians, on the other hand, believe that multipliers are less than 1 and that increases in government spending don't grow the economy by as much as their cost. The IMF has long been in the <1 camp (of course, as a lender of last resort, it's sort of their job to think that way).

So we have this multiplier, which pretty much everyone thinks exists, but the size of it has a lot of implications for policy. If it's less than 1, fiscal stimulus isn't a great idea and it's actually a good time for fiscal consolidation. If the fiscal multiplier greater than 1, we should open the Keynesian stimulus floodgates in order to end this depression now. I'll let the IMF's Chief Economist take it from here (Emphasis mine):

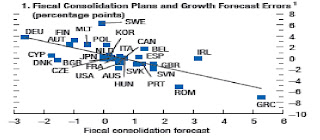

But fiscal consolidations have been more costly than realized, and they have a chart to show that

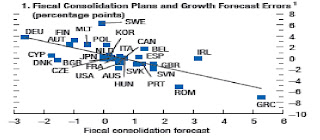

I also really like this chart, though it is from the unabashedly partisan Brad Delong and not something the IMF used

But why has this been so? The IMF is back,

In other words, fiscal policy may act differently in depressions than in boom times. This makes sense, there isn't exactly a lot of private investment for government borrowing to be crowding out today. Monetary policy may play a role as well; a low multiplier seems very plausible when Alan Greenspan says he'll lower interest rates in exchange for deficit reduction but when monetary policy is committed to working alongside and not against fiscal policy, a larger multiplier seems obvious. I don't expect to see Rick Santelli get on TV and say "Wow I blew my load over some pretty bad economics."

Another current IMF report weighs in:

Even in light of larger-than-realized multipliers, the IMF can't entirely shake its institutional bias in favor of austerity and advise countries with with low borrowing costs to forget austerity instead of "smoothing" it, but that's part of its institutional makeup and culture; dear reader, it need not be a part of your thinking.

The findings from the IMF suggest that Obama, DeacMan, jhmd, 2&2, DODO, Romney, Ryan, and ESPECIALLY Pete Peterson and Erskine Bowles are all barking up the wrong tree. We don't need to fiscal consolidation in the short term, we need J-O-B-S JOBS and they way to get them is through stimulus, as much monetary stimulus as we can do, and as much fiscal stimulus as possible. There's a scheduled payroll tax increase later this year, hopefully politicians will remove their heads from their anuses and cancel that. That would be a good start.

The IMF has released their new World Economic Outlook. It's gloomy, but there's a fascinating (maybe?) bit at the end of Chapter 1 - Box 1.1, "Are We Underestimating Short-Term Fiscal Multipliers?," co-written by the IMF's chief economist - that deals with the all-important fiscal multiplier. Essentially, Keynesians believe that multipliers are larger than 1 at certain times and government spending will boost economic output in those conditions. If you can spend $100B to get, say, a 125B increase in GDP, that's a good deal. Austerians, on the other hand, believe that multipliers are less than 1 and that increases in government spending don't grow the economy by as much as their cost. The IMF has long been in the <1 camp (of course, as a lender of last resort, it's sort of their job to think that way).

So we have this multiplier, which pretty much everyone thinks exists, but the size of it has a lot of implications for policy. If it's less than 1, fiscal stimulus isn't a great idea and it's actually a good time for fiscal consolidation. If the fiscal multiplier greater than 1, we should open the Keynesian stimulus floodgates in order to end this depression now. I'll let the IMF's Chief Economist take it from here (Emphasis mine):

[A] debate has been raging about the size of fiscal multipliers. The smaller the multipliers, the less costly the fiscal consolidation. At the same time, activity has disappointed in a number of economies undertaking fiscal consolidation...

The main finding, based on data for 28 economies, is that the multipliers used in generating growth forecasts have been systematically too low since the start of the Great Recession, by 0.4 to 1.2, depending on the forecast source and the specifics of the estimation approach. Informal evidence suggests that the multipliers implicitly used to generate these forecasts are about 0.5. So actual multipliers may be higher, in the range of 0.9 to 1.7.

But fiscal consolidations have been more costly than realized, and they have a chart to show that

I also really like this chart, though it is from the unabashedly partisan Brad Delong and not something the IMF used

But why has this been so? The IMF is back,

If the multipliers underlying the growth forecasts were about 0.5, as this informal evidence suggests, our results indicate that multipliers have actually been in the 0.9 to 1.7 range since the Great Recession. This finding is consistent with research suggesting that in today’s environment of substantial economic slack, monetary policy constrained by the zero lower bound, and synchronized fiscal adjustment across numerous economies, multipliers may be well above 1 (Auerbach and Gorodnichenko, 2012; Batini, Callegari, and Melina, 2012; IMF, 2012b; Woodford, 2011; and others). More work on how fiscal multipliers depend on time and economic conditions is warranted.

In other words, fiscal policy may act differently in depressions than in boom times. This makes sense, there isn't exactly a lot of private investment for government borrowing to be crowding out today. Monetary policy may play a role as well; a low multiplier seems very plausible when Alan Greenspan says he'll lower interest rates in exchange for deficit reduction but when monetary policy is committed to working alongside and not against fiscal policy, a larger multiplier seems obvious. I don't expect to see Rick Santelli get on TV and say "Wow I blew my load over some pretty bad economics."

Another current IMF report weighs in:

Countries that have more room to maneuver should let automatic stabilizers operate around the path currently envisaged in cyclically adjusted terms. Should growth disappoint, the first line of defense should be monetary policy and the free play of automatic stabilizers. If growth should fall significantly below current World Economic Outlook (WEO) projections, countries with room for maneuver should smooth their planned adjustment over 2013 and beyond

Even in light of larger-than-realized multipliers, the IMF can't entirely shake its institutional bias in favor of austerity and advise countries with with low borrowing costs to forget austerity instead of "smoothing" it, but that's part of its institutional makeup and culture; dear reader, it need not be a part of your thinking.

The findings from the IMF suggest that Obama, DeacMan, jhmd, 2&2, DODO, Romney, Ryan, and ESPECIALLY Pete Peterson and Erskine Bowles are all barking up the wrong tree. We don't need to fiscal consolidation in the short term, we need J-O-B-S JOBS and they way to get them is through stimulus, as much monetary stimulus as we can do, and as much fiscal stimulus as possible. There's a scheduled payroll tax increase later this year, hopefully politicians will remove their heads from their anuses and cancel that. That would be a good start.

Last edited: